Subject: Z

Date: March 12, 1987

Clinician: Dr. Sabine Leeren, PhD

Institution: Glen Sighing Cognitive Development Center

Reflections on Communication Milestones and Identity Formation in Subject Z

It is perhaps time I concede what may be considered my first professional failure. In my earlier years of practice, I was reluctant to believe in the notion of “failure” as it pertains to developmental psychology. I was inclined to regard such outcomes as alternative pathways to success. However, after years of direct observation and intervention with Subject Z, I am compelled to acknowledge that, in some respects, I have failed. Yet paradoxically, I have also succeeded.

Subject Z has been documented as predominantly nonverbal for the majority of his life. Extensive therapeutic modalities were employed to stimulate verbal communication: auditory exposure to literature, diverse musical engagement, structured peer interactions, and multimodal sensory interventions. Despite these efforts, Subject Z remained silent. Consultation with my colleague, Madame Talia Serrula, yielded the professional consensus that Z may never develop typical speech patterns. In hindsight, I recognize my fixation on eliciting verbal communication may have limited exploration of alternative communicative frameworks.

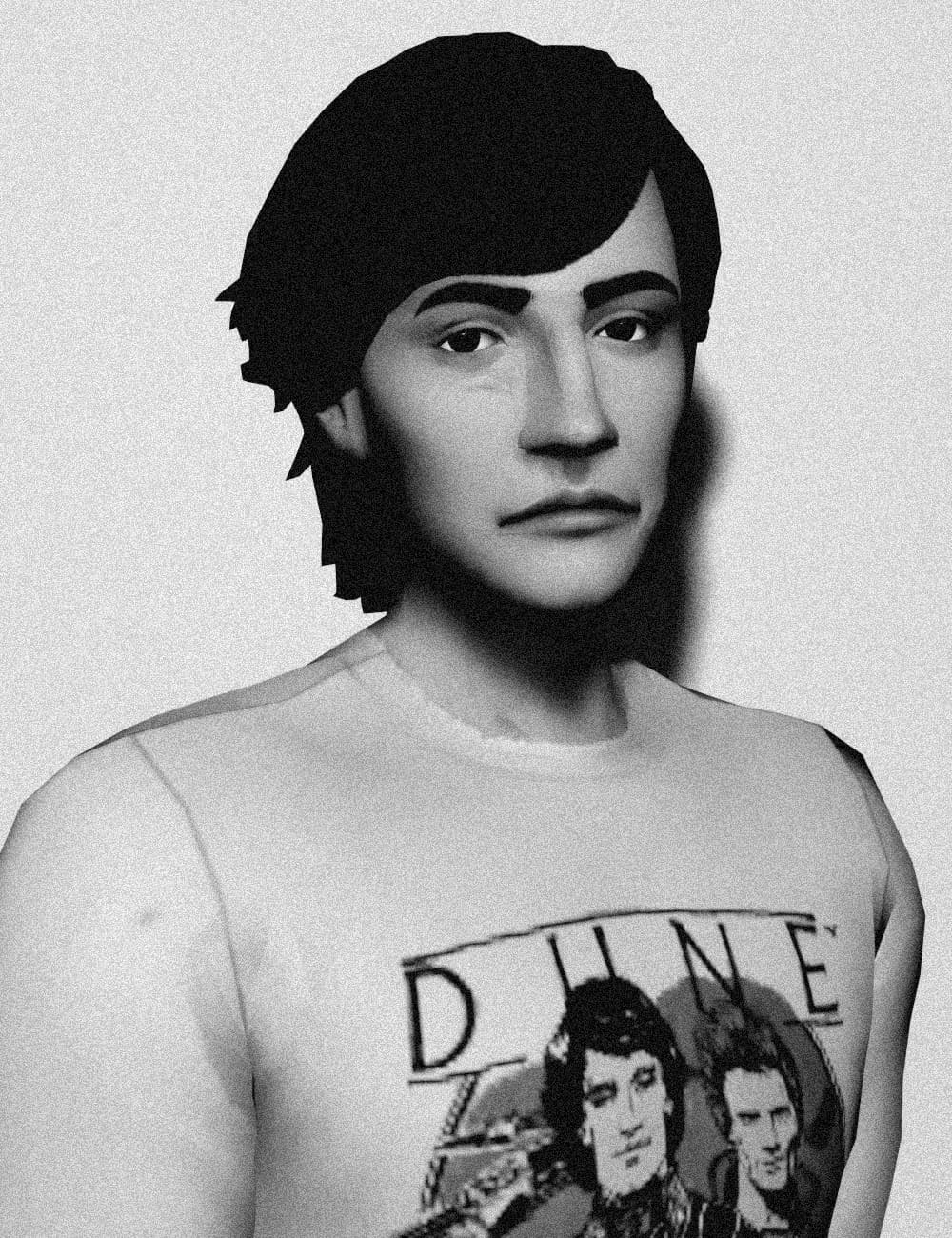

A critical incident occurred on December 25, 1984. During the annual holiday event, an administrative oversight led to Subject Z inadvertently receiving a VHS copy of Dune (1984) rather than the intended speech development material. The children were dismissed to engage with their respective gifts. Approximately one hour later, I was summoned by the sound of Subject Z’s proclaiming that “[his] name is a killing word.”

Upon entering the common area, I observed Subject Z exhibiting highly animated behavior—leaping over furniture, vocalizing with vigor, and demonstrating physical agility previously uncharacteristic of his baseline presentation. It became evident that he had absorbed the narrative content of Dune to an extraordinary degree, reportedly re-watching the film multiple times that same day.

Subsequent assessments revealed that Subject Z would respond exclusively using direct quotations from the film. When prompted for his name, he would consistently state, “I am Paul.” In alignment with this self-identification, I have since amended his case file to refer to him accordingly. Initially skeptical of the film’s influence as the catalyst for his verbal breakthrough, I have nonetheless observed sustained linguistic and cognitive advancement through the provision of Dune-related paraphernalia, including read-along books, graphic novels, and educational activity sets sourced from second-hand retailers.

Notably, this intervention yielded measurable improvements in academic performance, social engagement, and self-efficacy, albeit occasionally expressed with a degree of theatrical grandeur. Over time, I have come to appreciate the possibility that Subject Z’s cognitive architecture is exceptionally absorptive; his “psychic sponge,” if you will. It remains unclear whether his apparent mimicry is a discrete ability or merely a manifestation of an underlying neurocognitive plasticity.

Of particular interest is the physical resemblance Subject Z has developed to the protagonist Paul Atreides, which is, frankly, striking. Whether this is coincidental or the result of self-stylization remains under investigation. At present, there is insufficient evidence to formally categorize this as a dissociative identity phenomenon, though I remain open to revisiting this assessment pending further developmental changes, particularly as Subject Z now navigates the psychosocial complexities of adolescence.

One emergent theme in recent counseling sessions is his self-professed quest to locate his “Chani,” a reference I understand to be derived from the film’s romantic subplot. This preoccupation with fulfilling a perceived destiny has become a recurring therapeutic focal point. I have encouraged him to redirect his ambitions toward his recent acceptance into the Psychic Ambassadors Program, though the allure of a prophecy appears to retain significant psychological weight for him.

As a note for future review, I intend to consult Agent Maudlin regarding the ongoing mentorship dynamic between them. Through the Mindwalkers’ Post-C Adoption Initiative, they have been formally connected for nearly a decade, though their relationship retains a somewhat perfunctory character. Curiously, Subject Z (Paul) has recently formed a considerable attachment to Maudlin, seemingly inspired by the phonetic resemblance between the agent’s surname and the film’s “Muad’Dib” moniker. It is conceivable that this linguistic parallel may serve as a foundation for a more substantive rapport moving forward.

At present, Subject Z continues to demonstrate exceptional cognitive flexibility and an enduring commitment to his adopted persona. Whether this is to be classified as mimicry, narrative immersion, or emergent psychic proficiency remains an open question.

Further monitoring is advised.